USAID Funding Saved Millions of Children’s Lives. Recent Cuts Put It in Jeopardy

USAID investments significantly reduced deaths among children under age five and women of reproductive age, studies show

Tigray people, fled due to conflicts and taking shelter in Mekelle city of the Tigray region, in northern Ethiopia, receive the food aid distributed by United States Agency for International Development (USAID) on March 8, 2021.

Minasse Wondimu Hailu/Anadolu Agency via Getty Images

President Donald Trump and Elon Musk have made it their mission to slash funding and staff at federal agencies, and so far, this has perhaps been most damaging to the U.S. Agency for International Development, or USAID. As soon as he was inaugurated on January 20, Trump signed an executive order halting all foreign aid for 90 days. Weeks later the New York Times reported his administration planned to downsize the agency from more than 10,000 workers to 290. Most recently, Secretary of State Marco Rubio said that the Trump administration was canceling 83 percent of USAID programs and folding the rest under the Department of State.

The cuts have been fast and sweeping. “We spent the weekend feeding USAID into the wood chipper,” Musk posted on February 3 on X (formerly Twitter), the social media site he owns.

The effects of these actions immediately ricocheted around the world, and they will continue to be felt for years to come. They will especially threaten young children and women, for whom USAID funding has been providing lifesaving basic medical services that have ranged from vaccines to treatments for diarrheal diseases to maternal health care. Studies show this funding has helped save the lives of nearly three million children under age five and at least one million women of reproductive age in recent decades, experts say.

On supporting science journalism

If you’re enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Dismantling USAID endangers all of these gains. “This is like trying to pause an airplane in midflight and then subsequently firing the crew,” says Atul Gawande, former head of global health at USAID.

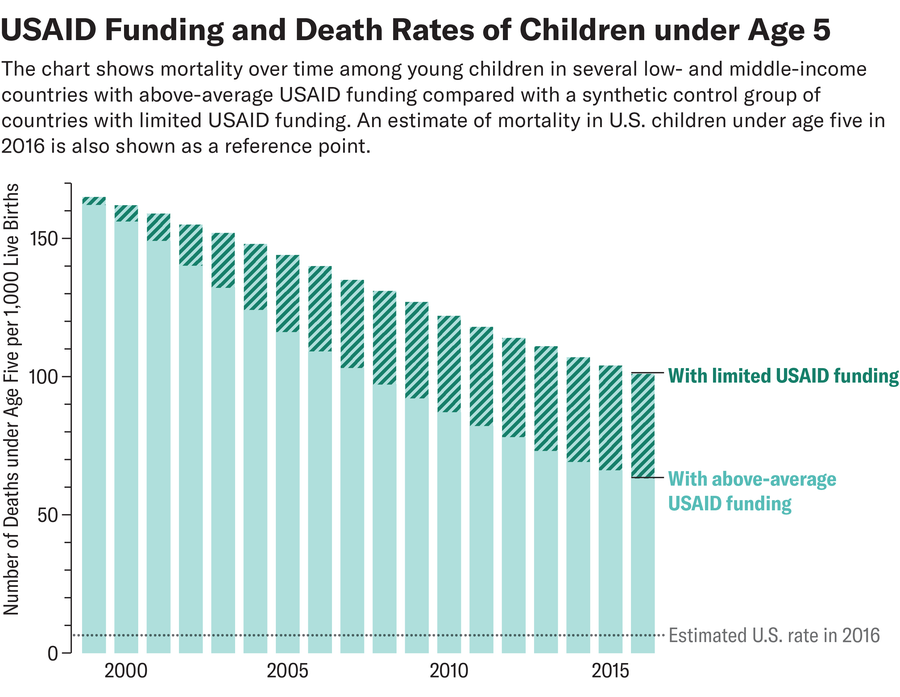

USAID has provided health funding and staff support to numerous countries worldwide. But measuring the effects of that aid—or the sudden lack of it—is a challenge. To do so, William Weiss, a professor at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health who served as an advisor in the global health bureau at USAID until his agreement was recently suspended, and his colleagues created a model to quantify the effect of USAID funding from 2000 to 2016 on under-five childhood mortality for low- and middle-income countries. The study was published in January 2022 in Population Health Metrics.

Because teasing out the specific effects of USAID funding from that other aid work is very challenging, Weiss and his colleagues used a method called a “synthetic control” analysis to estimate childhood mortality retrospectively across a group of countries that did and didn’t receive significant amounts of USAID funding. The researchers compared a “treatment” group of countries that received a high level of USAID funding for maternal and child health and malaria during the study period of 2000 to 2016 with a “synthetic control” group of similar countries that did not receive this level of funding.

The study found that countries that received above-average levels of USAID funding had, on average, 29 fewer deaths per 1,000 live births than the synthetic control group of countries that didn’t receive funding. That works out to roughly 500 fewer deaths per day, Weiss says. Additionally, the researchers found that the more USAID funding countries received over time, the bigger the benefit was—suggesting a dose-response effect.

“The message we were trying to send to leadership in the Congress was to say, ‘This is what you get when you significantly fund a country over a sustained period,’” Weiss says.

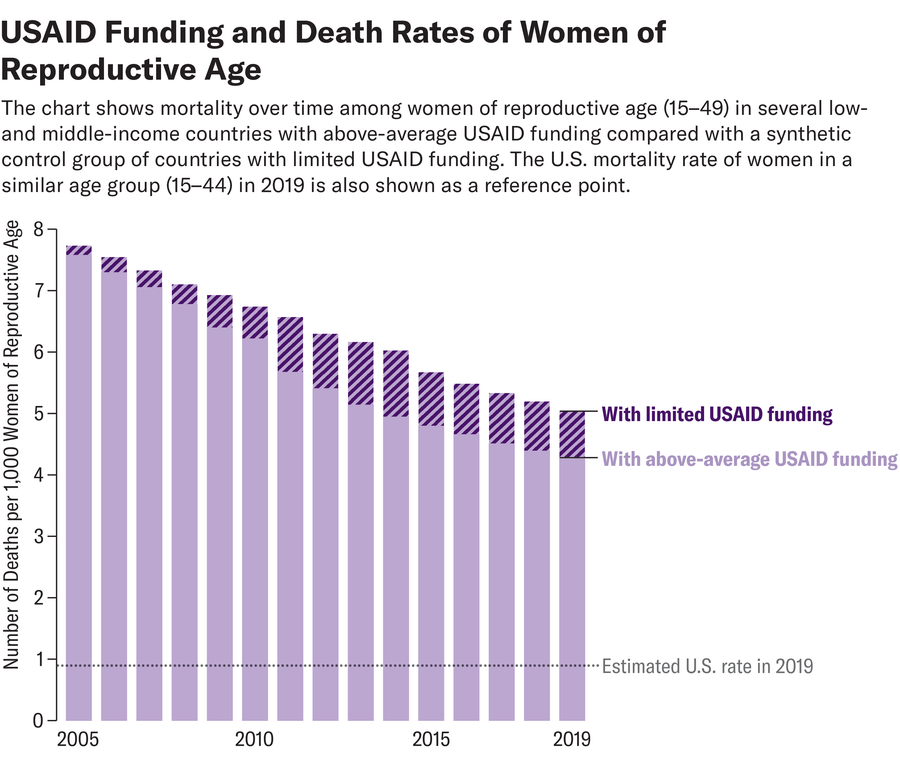

In a related preprint study posted online last August, Weiss, Gawande and their colleagues modeled the effects of USAID funding on mortality among women of reproductive age between 2005 and 2019. That study, which has been accepted for publication in the Journal of Global Health, found that for the years 2009 through 2019, countries that received a sustained high level of USAID funding saw a mortality rate reduction of 0.8 death per 1,000 women of reproductive age. This translates to about one million to 1.3 million deaths prevented, or four extra years of life expectancy, says Gawande, who is a surgeon at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, as well as a writer and public health researcher.

With the Trump administration gutting USAID, many of these longevity benefits could disappear. And while the administration has claimed the cuts are meant to prevent government waste, Americans largely support foreign aid.

“This has always been extremely bipartisan,” Weiss says of foreign health aid. “Congress and their constituents [have long been] behind these programs saving children’s lives, especially in poor countries, with interventions that were fairly cheap,” he says. “This is what the American people wanted, across ideological lines.”

The U.S. Department of State, which is now overseeing USAID, did not respond to a request for comment.

Troy Jacobs is a pediatrician and served as a senior medical adviser for maternal and child health at USAID for more than 17 years. “As a pediatrician, the whole reason that I joined USAID was that the solutions to some of the most wicked global health problems in maternal and child health are not totally within the biomedical space,” he says. Before he was terminated at beginning of February, Jacobs was working in Ethiopia to provide lifesaving maternal and child health care. “In countries like Ethiopia, where there’s a high burden-of-disease bill for infectious diseases, as well as growing chronic diseases like mental health issues and things like that, there was so much work to be done—but we were making progress,” dramatically reducing mortality among children under the age of five, he says. Now all that work has been put on hold.Jacobs’s colleagues in Ethiopia are telling him the cuts have caused a lot of hardship and confusion, he says. “And in that confusion, services are being delayed. People are not able to access resources,” he adds. “Globally, we’re estimating 95 million people [have been affected by] the loss of basic medical services.”

The USAID cuts have affected more than just funding for children’s and women’s health. They have terminated the President’s Malaria Initiative, which was protecting 53 million people from disease and death through the use of bed nets, diagnostics and treatments, according to Gawande. They have ended all work on tuberculosis, including funding for most TB treatment. And they have halted USAID contracts that administer funding from the U.S. President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR), the landmark HIV program launched by then president George W. Bush in 2003 and funded with bipartisan support by Congress ever since. PEPFAR has been providing medication to 20 million people worldwide.

Anna Katomski was hired as a program analyst in the HIV/AIDS office at USAID’s global health bureau, but she was laid off in late January after just two weeks. She was supposed to work on a PEPFAR-funded project called Maximizing Options to Advance Informed Choice for HIV Prevention (MOSAIC), with the purpose of scaling up HIV prevention for adolescent girls and young women in sub-Saharan Africa. The project was aimed at testing various approaches to HIV prevention, including a long-acting injectable form of pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP).

“So much of this work is either stopped because of USAID putting out its funding or will be stopped very soon,” Katomski says. And these long-acting medications have to be tapered off—you can’t just stop them cold turkey and switch to a pill, she notes. This could leave girls and young women vulnerable to HIV infection. “If, say, one of these adolescent girls or young women engage in in unprotected sex, for example, with a person with a penis who has HIV, they are at high risk of contracting the disease,” Katomski says. “HIV incidence is going to soar.”

On March 5 the Supreme Court ruled 5-4 that the Trump administration could not freeze about $2 billion in foreign aid. A federal judge later specified a date by which the administration had to pay back payments to USAID contractors for work that was already completed, but the decision doesn’t address future payments.

The Supreme Court’s ruling is important, but “the damage has already been done,” Gawande says. “Many of these organizations have already terminated most of their staff. They’re barely standing as organizations, but getting their payments that are past due would at least divert bankruptcy and make sure people’s pensions can be funded and things like that.” The question is what the Court will do now, he says, “because [the Trump administration has] dismantled the agency, and the ruling needs to be enforced somehow.”