Newfound Exoplanets around Barnard’s Star Resolve Long-Standing Astronomical Quest

Four small, newly discovered worlds are less than six light-years away from Earth, and their discovery reinforces a cautionary tale from planet hunting’s prehistory

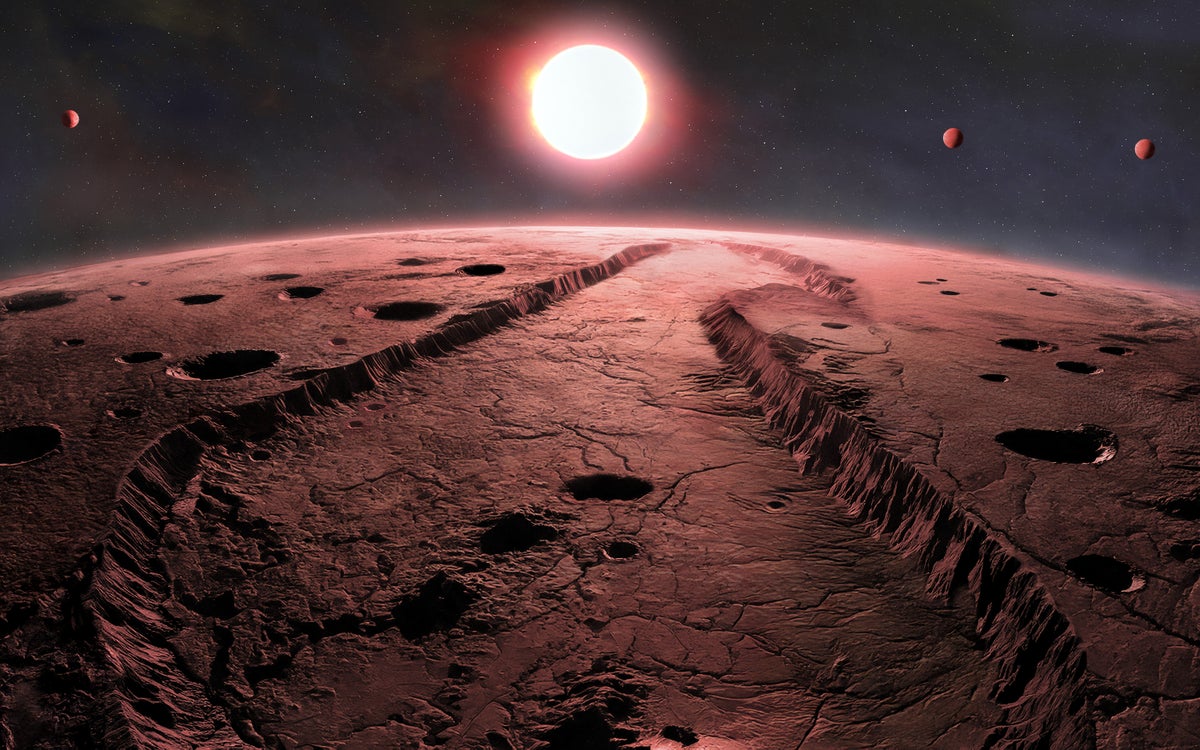

An artist’s impression of four small, likely rocky exoplanets orbiting Barnard’s Star, a red dwarf star about six light-years away from Earth.

International Gemini Observatory/NOIRLab/NSF/AURA/P. Marenfeld

Astronomers have confirmed the existence of four small planets around Barnard’s Star, one of Earth’s nearest and perhaps most notorious neighboring stars.

The new discoveries verify a study last year that suggested Barnard’s Star was orbited by at least one planet; the worlds were discovered using the radial velocity method, which can detect otherwise hidden exoplanets via a subtle wobble that their orbital tugging causes in motions of their host stars. The frequency of that stellar wobble reveals an exoplanet’s orbital period and distance from its star, and its strength provides an estimate of the unseen world’s mass.

The observations indicate that each of the four planets around Barnard’s Star is much smaller than Earth—between 20 percent and 30 percent of its mass. That means they are probably rocky, like the inner planets of our solar system. But they all orbit so closely to Barnard’s Star that they would be too hot for life as we know it.

On supporting science journalism

If you’re enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Besides their close proximity to Earth, these worlds are also noteworthy for being among the smallest yet found via the radial velocity method. In recent years, “the instruments have grown to give an unprecedented precision in radial velocities,” says astrophysicist Ritvik Basant, a doctoral student at the University of Chicago and lead author of a study in the Astrophysical Journal Letters that confirms the exoplanets.

The researchers are using the MAROON-X spectrograph on the Gemini North telescope in Hawaii to look for the radial velocity wobbles of exoplanets around nearby stars. “We have been taking data for the last three years,” Basant says.

Discovered in 1916 by American astronomer Edward Emerson Barnard, Barnard’s Star is a small and slow-burning red dwarf classified by astronomers as an M-type star. It is about six light-years away but only has about 15 percent of the mass of our sun; this makes it very faint despite its nearness to our solar system, and it cannot be seen in the sky by the unaided eye.

After its discovery, the next time Barnard’s Star made headlines was in 1963, when Dutch astronomer Peter van de Kamp declared he’d found evidence that it was orbited by a planet with about 1.6 times the mass of Jupiter. No exoplanets had been confirmed at the time, so van de Kamp’s announcement was an important event. Van de Kamp had observed Barnard’s Star for more than a quarter century prior to his announcement, and he claimed he’d seen a periodic perturbation in the star’s motions that was caused by the orbiting planet. Subsequent studies showed that these signs of van de Kamp’s “planet” actually came from minor spatial shifts of components in his telescope caused by their occasional maintenance. The debunking cast a shadow over planet-hunting for generations, but van de Kamp nevertheless championed his “discovery” for many years until his death in 1995.

The latest finds around Barnard’s Star have little to do with this earlier saga—other than reinforcing how this historic episode should be considered a cautionary tale. But they have set a new benchmark for the detection of small exoplanets around nearby stars, Basant says. The observations suggest that the planets orbit Barnard’s Star in a plane almost edge on to Earth. They don’t pass directly in front of the star as seen from our planet, however—such transits would be useful for determining each world’s exact size and even details of its atmospheric composition. Still, Barnard’s Star is so close that it may be possible to take their pictures in a difficult process called “direct imaging,” which involves blotting out most of a star’s light so that the far fainter light from any accompanying planets can be seen.

The observations also indicate that all four planets orbit only a few million miles from Barnard’s Star —much closer than the average 36-million-mile distance of Mercury from our sun. The nearest zips around completely in just two and a half Earth days at a distance of roughly 1.7 million miles, while the farthest orbits in less than seven days at a distance of about 3.5 million miles.

Similar compact systems of small planets have been detected around many other red dwarf stars, which are the most common stars in the universe, says Rice University planetary scientist André Izidoro, who was not involved in the study. Izidoro and his Rice University colleague Sho Shibata have used exoplanet data from NASA’s Kepler space telescope to create an updated model of planetary formation that may account for these smaller star systems. Their new model, which was also published recently in the Astrophysical Journal Letters, proposes that smaller planets mostly arise from impacts in rings of debris that from in whirling disks of gas and dust that surround nascent stars, while larger planets are usually born further out from a star, where the colder temperatures offer more abundant frozen material for world-building.

In the case of Barnard’s Star, Izidoro says it is likely the four planets had formed farther away than they are now but migrated inward because of gravitational interactions with the protoplanetary disk from which they first emerged. It is still possible that other rocky planets may lurk undiscovered around Barnard’s Star in more distant orbits, he says, where conditions would be cooler and perhaps even suitable for life.